In the last couple of posts we’ve been trying to define knowledge — and discovering, slightly painfully, that philosophers can’t agree on a definition without immediately inventing a counterexample involving barns, jobs, or both.

So now we move on to the next big question for the AQA Philosophy course (or at least, the Epistemology module):

Even if knowledge exists… where does it come from?

AQA starts with perception — which feels sensible, because perception is the most obvious way the world gets into your mind. You look. You hear. You touch. You know.

Except… it’s not that simple, is it?

Perception is brilliant, but it’s also:

- vulnerable to illusion

- vulnerable to hallucination

- vulnerable to variation

- and occasionally vulnerable to the awkward fact that light takes time to travel (so you might be seeing the past)

So for today’s revision, we’re going to look at three big theories:

- Direct realism: you perceive the world itself, directly

- Indirect realism: you perceive sense-data (mind-dependent), which represent a mind-independent world

- Berkeley’s idealism: the “mind-independent world” bit is the mistake — reality is mind-dependent

And yes, you are allowed to think: why are we doing this to ourselves? But AQA loves it, so here we are.

A quick starter thought experiment

Look at your laptop (or phone). Now ask yourself:

How do you know it exists when you’re not looking?

And — more awkwardly — how do you know you’re seeing the laptop itself, rather than something mental that merely represents it?

That question is basically the whole unit. And here are the main ways we can approach it…

1) Direct Realism

The core claim

The immediate objects of perception are mind-independent objects and their properties.

So:

- there really is a table

- it really is rectangular

- and when you perceive it, you are directly aware of that table, not a mental proxy

Direct realism is also called naïve realism (which sounds rude, but it’s just a label).

Why direct realism is tempting

Because it matches how experience feels.

When you look at a tree, it doesn’t feel like you’re looking at an internal “tree-image”. It feels like you’re looking at… a tree.

So direct realism wins big points for:

- common sense

- simplicity

- avoiding a “veil” between you and the world

Unfortunately, it then meets the four horsemen of perceptual chaos.

Issues for direct realism (and how direct realists respond)

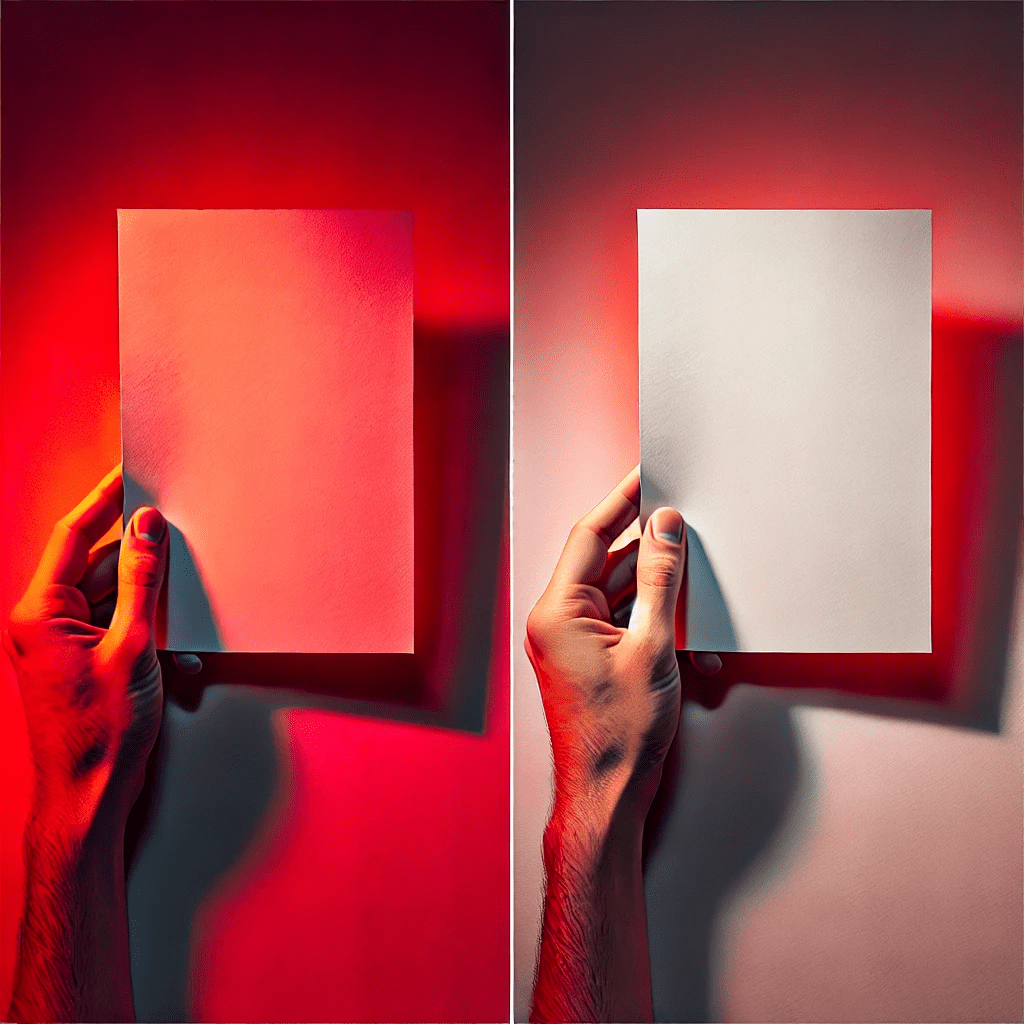

(1) The Argument from Illusion

Classic example: a straight stick looks bent in water.

The worry:

If perception is direct, why do objects sometimes appear to have properties they don’t really have? This is the argument from illusion.

Direct realist response (key AQA move):

Illusions show that objects can have relational properties like:

- looking bent-in-water

- looking smaller-at-a-distance

- looking red-under-this-lighting

So you are still seeing the physical object, just under conditions that make it look a certain way.

✅ This response is strong if you’re careful with the language:

- the object is still mind-independent

- but not all appearing properties are intrinsic properties

📌 Exam checkpoint (5 marks — SAMS style):

Explain one way a direct realist could respond to the argument from illusion.

For top marks, do:

- one-sentence outline of illusion

- then the relational property response

- then a quick line showing it preserves direct realism

(2) The Argument from Perceptual Variation (Berkeley & Russell)

A table looks darker in shadow, lighter in sunlight, different shades from different angles.

The worry:

If the table has a single real colour/shape/etc., why does it vary in experience?

Direct realist response:

Variation tells us more about:

- lighting conditions

- perspective

- our sensory limitations

than about whether the object is mind-independent.

In other words: the world can be stable even if your access to it isn’t.

(3) The Argument from Hallucination

Sometimes people have experiences that feel perception-like but aren’t caused by a real object at all. You could hallucinate you’re being chased through a city by a pink elephant… or anything else for that matter.

The worry:

If hallucination and genuine perception can feel identical, doesn’t that suggest the immediate object is the same kind of thing in both cases (something mental)?

This is often linked to the common factor principle:

If experiences are subjectively indistinguishable, they must share the same underlying kind of object.

Direct realist response:

Hallucinations aren’t perceptions of weird objects — they’re failures of the normal perceptual system. They also:

- don’t integrate well with other senses

- don’t respond reliably to actions

- lack the right causal connection to the external world

Some direct realists go further and reject the “common factor principle” entirely (this is where disjunctivist-style replies live), but you don’t need to name-drop to make the point:

Similar feel doesn’t guarantee same kind of thing.

📌 Exam checkpoint (5 marks — 2022):

Explain how the argument from hallucination presents an issue for direct realism.

AQA wants:

- clear definition of hallucination (non-veridical, can be indistinguishable)

- link to “direct objects aren’t mind-independent” worry

- why that pressures direct realism towards mediation/sense-data

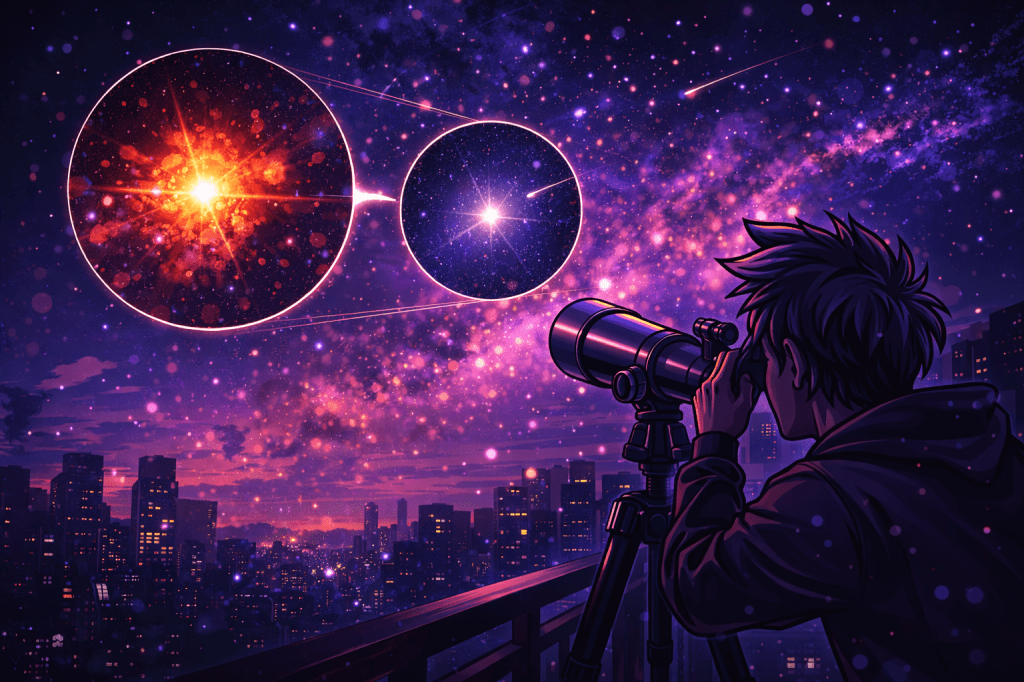

(4) The Time-Lag Argument (Russell)

Light takes time to travel. So when you see a star, you may be seeing it as it was ages ago.

The worry:

If you’re not perceiving the object “as it is now”, is perception really direct?

Direct realist response:

A time-lag is a causal delay, not a metaphysical “sense-data barrier”. You can still be directly aware of the object — just not simultaneously with the event.

This is a decent reply, but it doesn’t remove the overall pattern: direct realism keeps having to patch and qualify itself.

📌 Exam checkpoint (3 marks — 2023):

What is the difference between direct realism and indirect realism?

For 3/3, keep it precise:

- direct: immediate objects are mind-independent objects and properties (no mediation)

- indirect: immediate objects are mind-dependent sense-data, caused by and representing mind-independent objects (mediation)

2) Indirect Realism

Indirect realism basically says:

Direct realism is too neat. Real perception has a middle layer.

The core claim (AQA wording)

The immediate objects of perception are mind-dependent objects (sense-data) that are caused by and represent mind-independent objects.

So:

- mind-independent objects exist

- they cause sensory experiences

- but what you are directly aware of is sense-data (how the world appears to you)

This view is often associated with Locke.

Locke’s Primary and Secondary Qualities (and why AQA loves this)

Locke’s big move is to split properties into two kinds:

Primary qualities (mind-independent, in the object)

- shape

- extension/size

- motion/rest

- number

- solidity

These are the features objects have regardless of observers.

Secondary qualities (mind-dependent, in the perceiver)

- colour

- taste

- smell

- sound

- temperature (as experienced)

On this view, objects don’t contain “yellow” the way they contain “shape”.

They have the power to cause yellow-experiences in us.

📌 Exam checkpoint (5 marks — 2023):

Explain Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities.

To hit top marks:

- define “quality” as a power to produce ideas (you can paraphrase)

- give examples of each

- explain the key difference: mind-independent/intrinsic vs mind-dependent/power-to-produce-sensation

- add one Locke-style example (hot/cold hands; porphyry colour fading; etc.)

Locke’s Justification for Indirect Realism

John Locke developed indirect realism as part of his empirical philosophy, arguing that all knowledge comes through the senses. However, because perception is not always reliable, he distinguished between:

- The objective properties of things (primary qualities)

- The subjective aspects of experience (secondary qualities)

Locke’s key points:

- Primary qualities exist in objects themselves.

- A sphere’s roundness and solidity do not depend on being perceived.

- These properties exist whether or not a mind perceives them.

- Secondary qualities exist only in perception.

- A lemon is not inherently yellow or sour—those qualities depend on how human minds process sensory input.

- If there were no perceivers, color, sound, and taste would not exist as we experience them.

- Perception is involuntary, suggesting an external world.

- We cannot choose what we perceive—sensations are forced upon us (e.g., we cannot avoid feeling heat when touching a flame).

- This suggests that our experiences are caused by something external.

Why indirect realism feels scientifically “grown up”

Indirect realism fits nicely with the idea that perception involves:

- brains

- nerves

- light waves

- processing

It also handles illusion/variation more smoothly because it expects appearance to depend on conditions.

So what’s the catch?

The catch is… the “veil”.

The big issue: Scepticism and the Veil of Perception

If you only ever directly experience sense-data, then:

How do you know there’s anything beyond them?

You can’t step outside your own experiences to compare:

- “what’s in here” (sense-data)

with - “what’s out there” (mind-independent objects)

So indirect realism seems to lead to:

Scepticism about mind-independent objects

because we’re trapped behind the veil of perception.

AQA-friendly argument shape:

- If we only perceive sense-data, we never perceive physical objects directly

- If we never perceive physical objects directly, we can’t be certain they exist

- So indirect realism risks scepticism about the external world

Responses to scepticism (the ones AQA wants)

(1) Locke: The involuntary nature of experience

You can’t just decide what you’ll see next.

If perception were purely “mind-made”, experience would be more under your control.

So Locke argues:

the best explanation is that your experiences are caused by something external.

(2) Coherence of experience (Locke + Catharine Trotter Cockburn)

Your senses “line up” in structured ways:

- you see a mug

- you reach for it

- you feel it where you expected it to be

- you can walk around it and keep tracking it

This kind of cross-sensory and behavioural coherence makes more sense if there’s a stable external world causing your perceptions.

(3) Russell: External world as the “best hypothesis”

Even if we can’t get absolute proof, positing an external world is:

- simpler

- more predictive

- more consistent with the orderliness of experience

So it’s rational to treat the external world as the best explanation.

📌 Exam checkpoint (12 marks — 2022):

Outline indirect realism and explain Berkeley’s objection that mind-dependent ideas cannot be like mind-independent objects.

AQA wants two halves:

- AO1: clear explanation of indirect realism + sense-data + representation

- AO2: Berkeley’s “likeness” worry (below) applied directly

Which brings us neatly to…

3) Berkeley’s Idealism

Berkeley looks at indirect realism and says, essentially:

“You’ve admitted you only ever experience ideas/sense-data… so why pretend there’s a material world behind them?”

The core claim

The immediate objects of perception (tables, chairs, etc.) are mind-dependent objects.

Reality is made of:

- ideas (what’s perceived)

- and minds/spirits (perceivers)

His famous slogan is often given as: to be is to be perceived — but the important thing is the argument behind it.

Berkeley’s attack on Locke’s primary/secondary distinction

Locke says:

- primary qualities are in the object

- secondary qualities are in the mind

Berkeley says:

You can’t separate them cleanly.

Argument idea:

- You never perceive shape/extension without some sensory qualities (colour, shading, texture, etc.)

- If secondary qualities are mind-dependent, then primary qualities are tangled up in the same dependence

- So the whole “primary are mind-independent” idea collapses

This is sometimes called a kind of conceptual dependence attack: your concept of shape isn’t floating free of sensory presentation.

A clean evaluation move (great for AO2):

You can point out a gap:

- “always perceived together” doesn’t automatically mean “dependent for existence”

That’s a solid critique if you explain it clearly.

Berkeley’s “Master Argument”

Try to think of an object that exists unperceived.

Berkeley claims:

- the moment you try, you’re thinking of it

- and therefore it’s in a mind

- so “unperceived object” is not a coherent idea

The standard objection (keep it Russell-ish)

Critics say Berkeley confuses:

- the act of thinking about a tree

with - the tree itself

Yes, your idea of a tree is in your mind.

It doesn’t follow that the tree must be.

Problems for idealism (and Berkeley’s replies)

(1) Illusion and hallucination

If everything is mind-dependent anyway, what marks out “real” experiences from illusory ones?

Berkeley’s reply:

- “real” experiences are more coherent, stable, predictable

- hallucinations are disordered, inconsistent, private-ish

This reply has some force, but students can push:

- coherence might be a useful practical test, but is it a truth test?

(2) Solipsism worry

If reality is just ideas and perceivers, how do you know other minds exist?

And does the world blink out when you close your eyes?

Berkeley’s answer is: God.

(3) The role of God (a big AQA focus)

Berkeley claims the world remains stable because:

- God perceives everything

- so objects continue to exist even when humans aren’t looking

But this creates exam-friendly problems:

- What does it mean for God to “perceive” if God doesn’t have bodily senses?

- If God can’t feel pain or have sensations, how can ideas “exist in God’s mind” in the way Berkeley suggests?

- Is God doing explanatory work here… or just being wheeled in to stop the theory collapsing?

📌 Exam checkpoint (3 marks — 2020):

Explain why there might be a problem with the role played by God in Berkeley’s idealism.

For 3/3:

- one clear sentence stating Berkeley needs God to secure continued existence

- one clear sentence explaining the tension (God non-sensory / perception language / ad hoc feel)

A common-sense punch: Moore’s “two hands”

In “Proof of the External World“, G.E. Moore’s basic move (paraphrased) is:

- “Here is one hand, and here is another — so external objects exist.”

In a bit more detail, here’s how he claims he can prove the existence of the external world:

“How? By holding up my two hands, and saying, as I make a certain gesture with the right hand, ‘Here is one hand’, and adding, as I make a certain gesture with the left, ‘and here is another’”

“I knew that there was one hand in the place indicated by combining a certain gesture with my first utterance of ‘here’ and that there was another in the different place indicated by combining a certain gesture with my second utterance of ‘here’. How absurd it would be to suggest that I did not know it, but only believed it, and that perhaps it was not the case! You might as well suggest that I do not know that I am now standing up and talking — that perhaps after all I’m not, and that it’s not quite certain that I am!”

The point isn’t that this is a magical knockout argument.

The point is that sceptical/idealist theories often start to look less plausible than the ordinary beliefs they’re trying to defeat.

It’s a reminder that:

sometimes philosophy is choosing between:

- a theory that is clever

- and a view that is livable

📌 Exam checkpoint (25 marks — 2021):

Is Berkeley’s idealist account of perception convincing?

AQA’s 25-mark essays reward:

- clear argument direction from the start

- strong AO1 (Berkeley’s arguments)

- ongoing AO2 evaluation (not just a big block at the end)

- weighing: what matters most? scepticism? coherence? God? common sense?

A really strong thesis is something like:

Idealism avoids scepticism about matter by removing matter, but it risks buying certainty at the price of plausibility.

So which theory should you back?

Here’s a revision-friendly way to hold it:

Direct realism

- Strengths: simplest, fits experience, avoids the “veil”

- Weaknesses: pressure from illusion/variation/hallucination/time-lag; needs careful responses

Indirect realism

- Strengths: explains variation and perceptual error neatly; fits with science; keeps external world

- Weaknesses: threatens scepticism (veil of perception)

Berkeley’s idealism

- Strengths: dodges external-world scepticism by making reality mind-dependent

- Weaknesses: solipsism pressure, “real vs illusion” worries, and God doing suspiciously heavy lifting

Quickfire revision questions

- What is the best argument against direct realism? Why?

- What is the strongest response to scepticism for indirect realism?

- What is Berkeley’s most powerful argument — and what’s the cleanest objection?

Content Wrap-up

Previously: We (attempted) to define knowledge, before looking at the issues with the traditional tripartite definition (JTB).

Next up: Reason as a source of knowledge — because once perception has thoroughly humbled us, AQA decides to ask whether reason can do better.

(It might. It also might not. Philosophy is like that.)

Support my work

Have you found this post helpful? By contributing any amount, you help me create free study materials for students around the country. Thank you!