For the next few posts, we’re diving into Epistemology — the part of the AQA A Level Philosophy course that asks some deceptively simple questions and then absolutely refuses to give you easy answers.

At the centre of it all is one question that sounds harmless enough:

What is knowledge?

You might think you already know the answer. (Irony fully intended.) But once philosophers get involved, things get complicated very quickly.

This first post is about laying the groundwork properly. No Gettier panic yet. No frantic counterexamples. Just a clear look at:

- the different kinds of knowledge, and

- the traditional attempt to define propositional knowledge — the famous justified true belief account.

Epistemology in One Sentence (Almost)

Epistemology is the branch of philosophy concerned with knowledge: what it is, how we get it, and whether we’re justified in claiming to have it at all.

Crucially, when philosophers argue about knowledge, they are usually not talking about skills or familiarity. They’re talking about something much narrower — and much more slippery.

So before definitions, we need to sort out what kind of knowledge we’re even discussing.

Three Types of Knowledge (And Only One Causes Trouble)

Philosophers typically distinguish between three kinds of knowledge. You probably already use all three in everyday language without noticing.

1. Acquaintance Knowledge – Knowing of

This is knowledge gained through direct experience or familiarity.

“I know Paris.”

“I know her quite well.”

You don’t need to be able to explain facts or give reasons here. You just need exposure. You’ve been there. You’ve met them. End of story.

2. Ability Knowledge – Knowing how

This is practical knowledge — being able to do something.

“I know how to ride a bike.”

“I know how to play the piano.”

Interestingly, you might be completely unable to explain how you do it. The knowledge shows itself in performance, not propositions.

3. Propositional Knowledge – Knowing that

This is the one philosophers obsess over.

“I know that Paris is the capital of France.”

“I know that the Earth orbits the Sun.”

This kind of knowledge involves claims that can be true or false. And that makes it perfect for philosophical scrutiny.

👉 When the AQA Epistemology specification talks about “the definition of knowledge,” it is talking about propositional knowledge. Always.

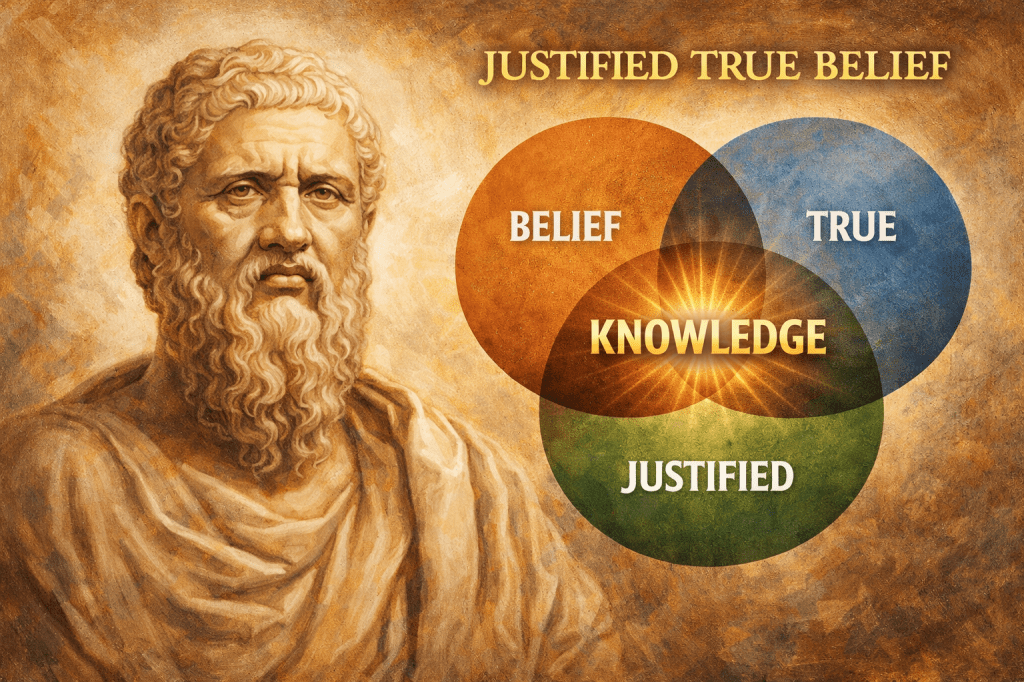

The Classic Definition: Justified True Belief (JTB)

The most famous attempt to define propositional knowledge comes from Plato, in Theaetetus.

The idea is simple, elegant — and, as it turns out, deeply controversial.

According to the tripartite view, a person S knows that a proposition p if and only if:

- p is true

- S believes that p

- S is justified in believing that p

Knowledge, on this account, is justified true belief.

Each part matters. Remove any one of them, and knowledge seems to disappear.

Why These Conditions Matter

Philosophers describe these conditions as individually necessary and jointly sufficient.

That sounds technical, but the idea is straightforward.

Truth

You can’t know something that’s false.

If someone says, “I know the moon is made of cheese,” we don’t politely disagree — we reject the claim to knowledge outright.

Belief

You can’t know something you don’t believe.

Even if a statement is true, it doesn’t count as your knowledge unless you actually accept it.

Justification

This is the most interesting (and controversial) part.

Suppose someone says, “I know this coin will land heads,” just before a fair coin is flipped. Even if they turn out to be right, we don’t usually want to call that knowledge — it’s a lucky guess.

Justification is meant to rule out accidental correctness.

Together, these three conditions look like they should do the job perfectly.

Unfortunately… they don’t.

A Brief Detour: What Makes a Good Definition?

Before things fall apart, it’s worth asking what philosophers think a definition should do in the first place.

A good definition should:

- capture all genuine cases of the thing being defined

- exclude things that aren’t really that thing

- avoid circularity (using the concept to explain itself)

This is where philosophers like Linda Zagzebski step in.

Zagzebski argues that knowledge may not be the sort of thing that behaves well under neat, rule-based definitions. She suggests that attempts to define knowledge often smuggle in the very idea they’re trying to explain — or exclude cases in an arbitrary way.

Her work pushes epistemology toward virtue-based approaches, where knowledge is linked to good intellectual character and reliable reasoning rather than tidy checklists.

That idea will matter a lot later. For now, keep it in the background.

The Big Problem: Gettier Cases

For centuries, justified true belief was treated as the definition of knowledge.

Then, in 1963, Edmund Gettier wrote a super short paper that changed everything. It’s essentially every PhD student’s dream.

Gettier described cases where someone has:

- a belief that is true,

- justified,

- and sincerely held —

yet still doesn’t seem to have knowledge.

The most famous example goes like this:

Smith and Jones apply for the same job.

Smith hears a reliable source say that Jones will get it.

Smith also sees Jones has ten coins in his pocket.

Smith forms the belief:

“The man who will get the job has ten coins in his pocket.”

But — unexpectedly — Smith gets the job.

And, by coincidence, Smith also has ten coins in his pocket.

Smith’s belief is:

- justified (based on strong evidence),

- true,

- and believed.

Yet it seems deeply wrong to say Smith knew this fact. He was right, but only through luck.

This is the fatal problem for the tripartite view:

justified true belief is not sufficient for knowledge.

Where This Leaves Us

At this point in the course, you should be clear on three things:

- Epistemology is concerned with propositional knowledge

- The traditional definition of knowledge is justified true belief

- Gettier cases show that this definition doesn’t fully work

And that raises the obvious question:

👉 If knowledge isn’t just justified true belief… what is it instead?

That’s where things get interesting — and where the rest of the epistemology course really begins.

In the next post, we’ll start exploring the attempts to fix JTB, beginning with no false lemmas, before moving on to reliabilism, infallibilism, and virtue epistemology.

Brace yourself. Philosophy does not let go easily.

Support my work

Have you found this post helpful? By contributing any amount, you help me create free study materials for students around the country. Thank you!